Bus travel lacks the glamour and comfort of driving or flying. But companies are hoping driverless technology will be the key to getting punters back on board with better facilities, more space and more frequent services.

Department for Transport figures showed UK bus journeys had fallen to 1.2bn, their lowest level in 12 years, between April and June this year. Going driverless could make buses more efficient, comfortable and cheaper to run, and change them from a tired last-resort mode of transport to one of the best ways of getting around.

Running buses at a lower cost could even bring back routes that are deemed uneconomical, particularly in rural areas. Partnerships between rural and urban areas could see cheap routes subsidising journeys in less populated areas.

Reimagine the bus

The first step may be to reimagine the bus entirely. Smaller, more frequent buses are less cumbersome on city streets and narrow rural roads, and mean customers don’t have to wait as long, but they are more expensive to run if they all need drivers.

Reilly Brennan of Trucks, a San Francisco-based venture capital fund that specialises in transport, says autonomy is the “perfect solution”. “The larger fleet providers are either going to have to make acquisitions or have to do some of this technology themselves, because the model is in many ways more efficient to have smaller, automated vehicles replacing the large vehicle routes,” he says.

Vehicles that run on predictable routes are easier to automate. A key stage in the development of self-driving software is mapping the routes, which enables vehicles to predict hazards, and identify road features such as traffic lights, roundabouts and junctions.

Urban bus routes tend to be low-speed, and the technology is even easier to develop if you add features such as a dedicated lane and sensors on street furniture.

“If you make the decision to go on the same route over and over again, you can get really proficient. So you can get increasingly better levels of automation. Then you can take it a step further because you can put sensors within the infrastructure,” says Mr Brennan.

Stagecoach

One established bus company exploring autonomous technology in the UK is Stagecoach, with a project on Scotland’s Forth Road Bridge due for 2020. In contrast to the futuristic “pod” model, their plan involves using a standard single-deck Stagecoach bus to run a public commercial service to level four autonomy – the stage below level five (understood to be the level at which a vehicle could safely pilot itself).

It will have a safety driver who will take over at challenging points, but will be mostly autonomous. Sam Greer, engineering manager, says: “We don’t know how our customers are going to react to being in a bus where the driver isn’t in full control 100pc of the time. How are other road users going to react?”

For long-distance buses, companies are looking at a part-driver, part-autonomous model. But they are also asking whether the back-up driver needs to be on the bus. German company FlixBus, which runs inter-city routes in Europe and the United States, is considering technology involving a virtual driver, who could take control from home or the office. Once on the motorway, the self-driving technology would take over.

Daniel Krauss, co-founder and chief information officer, thinks this hybrid model could be less than five years away, but the challenge is finding the right partner to provide the technology. The industry’s obsession with cars means finding a bus specialist is a challenge. Manufacturers are still focused on “where they can make the most money”, he says. “I think you’ll always see a slight advantage in technology adoption in cars and taxis than buses and trucks.”

There are other challenges with long-distance buses. The journeys are less predictable, with drivers charged with making more decisions, such as which exit to use from a motorway in order to avoid traffic.

But the potential benefits are significant. It could minimise hazards such as road-weary drivers, and could mean staff on board dedicated to customer service. “You basically can have a coffee at home while controlling buses through VR,” he says. “You may have more space in buses and increase the space for the customers. You could take the resources and distribute it differently, so you have more in-person stuff only focusing on serving the customers.”

The coffee-sipping VR bus driver and his pampered passengers seem a far cry from today’s long-distance coach services. Companies are determined to show their buses of the future are a force to be reckoned with. They currently suffer from “stigma” of being “inflexible and old-fashioned”, says Stagecoach’s Greer. “We want to demonstrate that it’s not. We can be at the cutting edge of technology.”

DB dabbles with Ollie

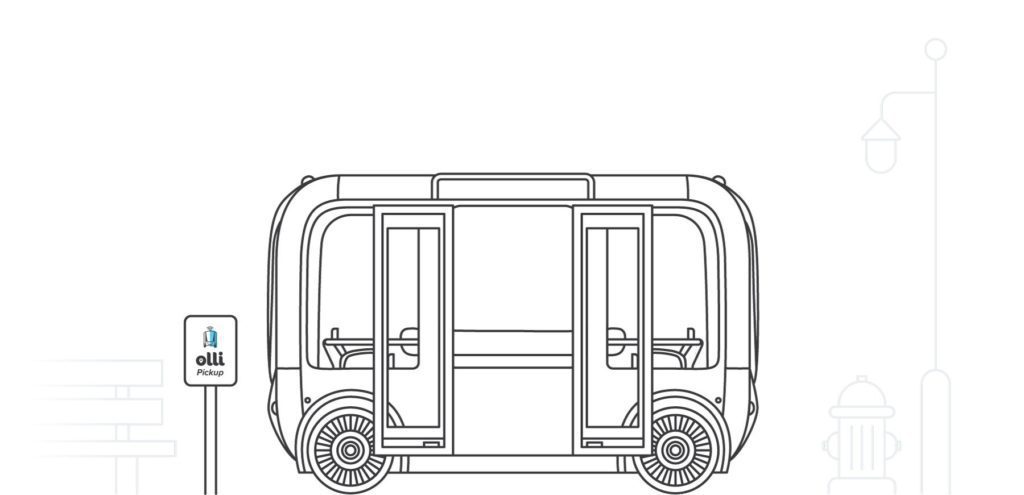

German Bus firm Deutsche Bahn experiments with driverless bus Ollie.

A prototype bus, nicknamed Olli and built by the US firm Local Motors, is currently undergoing testing in the Schöneberg district of Berlin, with plans in place to build 50 models.

Ollie provides space for 12 passengers and drives at speeds of up to 20 kilometres per hour.

When Olli hits the streets, passengers will be able to call him via an app and will then be able to chat with him about the weather, good cafes in the area, or the best public transport connections.

“In five years, hundreds of autonomous vehicles will be travelling the streets of Berlin waiting to be called into service,” Damien Declercq, executive vice president of Local Motors claims.

EasyMile

One other company playing with Auto Buses is France based EasyMile who have a dream for shared driverless mobility for communities.

Now with a number of Buses on trial in many locations they are trying to validate the business and feasibility prior to large scale roll out.

The most recent trial is down under in Australia at Coffs Harbour in New South Wales. The autonomous shuttle trial is also a first for regional New South Wales, and will be implemented in three phases over a 12-month period.

The EZ10 will be covered in different designs during the different phases of the trial, starting with the indigenous artwork depicting the sacred importance of Muttonbird Island to the local Gumbaynggirr people.

The trial will incorporate smart traffic lights, on demand operation, roundabout navigation and mixed traffic operations.

Sources

Local Motors the designer and manufacture of Olli.

Easy Mile. French Auto Bus company.